What has North Korea Gained Economically from the Russia–Ukraine War?

- Commentary

- May 13, 2025

- Seung-ho JUNG

- Incheon National University, School of Northeast Asian Studies

Seung-ho Jung, Professor of Incheon National University, contends that despite North Korea’s extensive provision of manpower and military materiel in support of Russia’s war in Ukraine, the resultant economic compensation has remained markedly limited. Professor Jung attributes the constraints impeding substantive economic cooperation between Pyongyang and Moscow to three principal factors: poor logistical infrastructure, lack of complementarity in trade structure, and the Chinese government's tepid attitude. This dynamic, he argues, suggests that North Korea’s primary objective in deepening ties with Russia lies not in securing economic benefits per se, but rather in gaining access to advanced military technologies. Accordingly, the author underscores the imperative for South Korea to adopt a more strategically calibrated diplomatic approach vis-à-vis China and Russia, given the limited economic ties between North Korea and Russia.

■ See Korean Version on EAI Website

1. Background

According to South Korea's National Intelligence Service (NIS) to the National Assembly's Intelligence Committee in 2025, over 4,700 North Korean personnel are estimated to have been killed or injured while supporting Russia in the war in Ukraine (Yonhap 04/30/2025). South Korea's Defense Ministry further estimated that more than 20,000 containers were shipped from North Korea's Rajin Port to Russia, noting that if these were filled with 152mm artillery shells, the total could amount to as many as 9.4 million rounds (Yonhap 10/23/2024).

Given such large-scale military support, what kind of economic returns has North Korea received in exchange? Some experts had anticipated that North Korea, suffering from intensified UN sanctions since 2017 and a prolonged border closure following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, might find an economic lifeline through its strengthened relationship with Russia. The war in Ukraine was thought to offer North Korea tangible benefits such as access to energy supplies and food aid.

However, an examination of economic indicators since late 2023, when military cooperation reportedly intensified, reveals little evidence of any significant "war dividend." This commentary assesses the economic impact of strengthened North Korea–Russia ties by analyzing macroeconomic indicators, such as market prices, and demonstrates structural constraints that limit the effect of such cooperation. It also offers policy implications for the international community.

2. Economic Impact of North Korea–Russia Cooperation

Labor exports have emerged as the most prominent area of North Korea–Russia economic cooperation. Facing a labor shortage and an urgent need for reconstruction in occupied territories, Russia is increasingly turning to North Korean workers, who are favored for their low wages and strict state-imposed discipline. The NIS estimated that around 15,000 North Korean workers had been sent to Russia. Labor exports provide some relief to North Korea's chronic foreign currency shortages. However, the revenues from these labor deployments are vulnerable to fluctuations in the Russian ruble. Since the outbreak of the war, the ruble has been steadily depreciating, suggesting that even if labor exports expand, the real value of remittances received by Pyongyang may remain limited.

Trade, another key channel of economic cooperation, is also difficult to assess due to limited data availability. Russia stopped publishing official trade statistics after the war began. Nevertheless, Yury Ushakov, an aide to President Putin, stated in 2023 that bilateral trade with North Korea had reached USD 34.4 million—nine times higher than the previous year (RFA 06/18/2024). Given the deepened cooperation in 2024, the actual figure may be significantly higher. Despite this rapid growth, the absolute scale of trade is still modest. Since 2010, Russia's share in North Korea's overall trade has consistently remained around 1 percent. Even the most recent figures fall short of the 2016 level of USD 76.9 million, recorded before the implementation of enhanced UN sanctions.

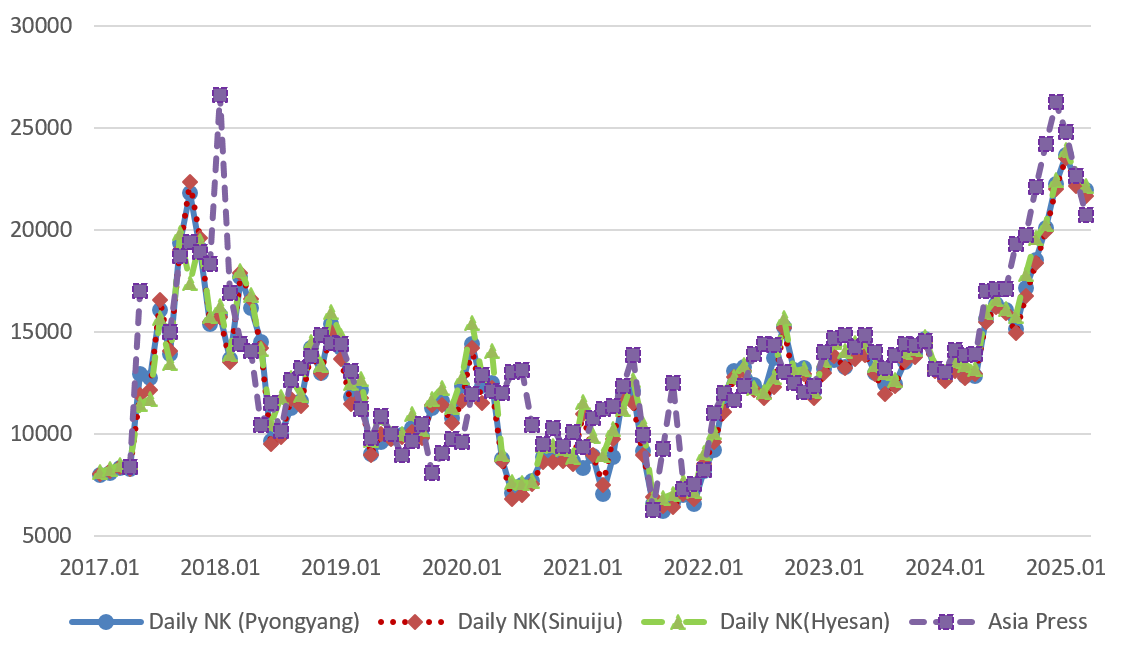

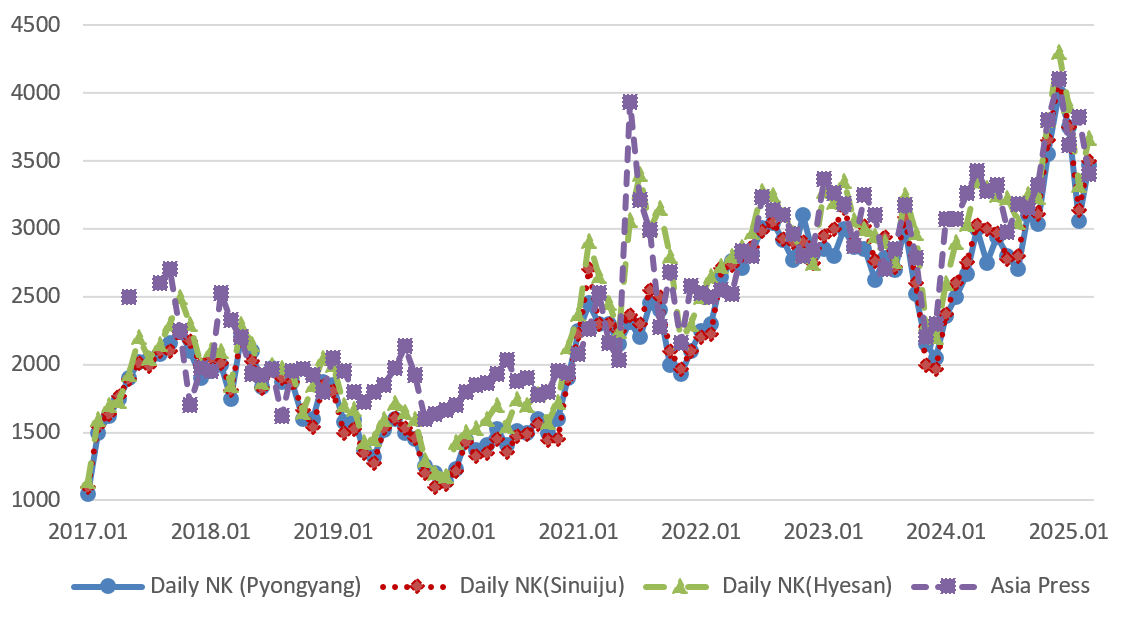

The extent to which Russian goods have entered North Korea's domestic markets can be indirectly assessed through market price trends. Russia is a major exporter of grain and refined petroleum, and if large-scale shipments had occurred, it is likely that prices of gasoline and corn in North Korea would have stabilized. Figures 1 and 2 show the market price trends of gasoline and corn in North Korea, based on data collected by two widely cited North Korea-focused media outlets: Daily NK and Asia Press. As seen in the figures, prices for both commodities continued to rise even after North Korea's military support for Russia intensified in 2024. While price fluctuations are influenced by various factors—including exchange rates, imports from China, and domestic demand—current data provide little evidence that Russian imports have had a noticeable stabilizing effect on North Korean markets.

Figure 1. Gasoline Prices in North Korean Markets (Jan 2017 – Mar 2025)

(Unit: North Korean Won)

Source: DailyNK, Asia Press

Figure 2. Corn Prices in North Korean Markets (Jan 2017 – Mar 2025)

(Unit: North Korean Won)

Source: DailyNK, Asia Press

3. Structural Constraints on Bilateral Cooperation

During President Putin's visit to Pyongyang in June 2024, the two countries signed a Treaty on Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, upgrading their 2000 Treaty of Friendship into a more robust strategic framework. The agreement called for enhanced cooperation in trade, investment, finance, and science and technology. Despite this diplomatic milestone, however, tangible economic outcomes have not yet been clearly observed. This is largely due to a number of structural constraints that continue to limit bilateral economic exchange.

First, poor logistics infrastructure and high transportation costs pose major challenges. While North Korea and China are connected by 12 border ports that include roads, railways, pipelines, and seaports, North Korea and Russia are linked only through a single checkpoint—the Tumen River–Khasan railway crossing. This route is hindered by incompatible rail gauges, outdated infrastructure, and limited freight capacity, making it unsuitable for large-scale cargo transportation. Furthermore, the long distance between Russia's industrial centers and North Korea significantly increases transportation costs, undermining the profitability of all but high-value trade.

Second, the structure of bilateral trade is not complementary. Russia is largely self-sufficient in key resources such as coal and iron ore, which are North Korea's main export items, leaving Pyongyang with few viable goods to offer. Moreover, North Korea lacks competitiveness in consumer goods like electronics and light industrial products, which Russia typically sources from more competitive suppliers such as China and Vietnam.

Third, China's cautious attitude presents another constraint on expanding trilateral cooperation. If China were to participate, three-party economic engagement could enhance logistics efficiency and integrate North Korea into regional supply chains. However, as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, China is unlikely to overtly violate UN sanctions. Moreover, given its interest in managing tensions with the United States, China has shown little inclination toward forming a trilateral bloc with North Korea and Russia, which could ultimately undermine its own strategic interests.

4. Conclusion and Policy Implications

A more fundamental reason for the limited economic gains from strengthened North Korea–Russia cooperation may be Pyongyang's preference for strategic—particularly military—compensation over economic benefits. North Korea appears to value access to advanced military technologies from Russia, especially those it is unable to develop or acquire on its own. These include reconnaissance satellite launch systems, drones, electronic warfare equipment, and air defense missile systems.

The international community must therefore extend its focus beyond core economic sanctions—such as those targeting labor exports and energy trade—and increase vigilance over military material transfers and technology cooperation. Efforts to prevent the expansion of North Korea's military-industrial capacity and to block the inflow of Russian military technologies must remain a top priority in the enforcement of UN sanctions.

South Korea should strengthen diplomatic engagement with both China and Russia. With China, Seoul must work to prevent the realization of a so-called North Korea–China–Russia bloc or a "new Cold War" narrative promoted by Pyongyang. Expanding practical cooperation in non-sensitive sectors, such as general-purpose technologies, can help stabilize bilateral ties. With Russia, diplomatic efforts should focus on blocking the transfer of military technologies to North Korea. South Korea can emphasize that, despite a postwar decline, bilateral trade still reached $15 billion in 2023, making it a much more significant partner than North Korea. Seoul can also highlight its potential role in the future development of Russia's Far East, presenting itself as a trusted partner and encouraging Moscow to exercise restraint in its military cooperation with Pyongyang. ■

References

Radio Free Asia (RFA). 2024. "Russian Media Reported Expectations for Putin's North Korea Visit (In Korean)." June 18. https://www.rfa.org/korean/in_focus/nk_nuclear_talks/2024russia-dprk_summit_june-06182024144454.html. (Accessed: May 13, 2025)

Yonhap News. 2024. "Ministry of Defense: 'Approximately 20,000 Containers Estimated to Have Been Transported to Russia via Rajin Port' (In Korean)." October 23. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20241023050300504. (Accessed: May 13, 2025)

Yonhap News. 2025. "National Intelligence Service: 'North Korean Troops Deployed to Russia-Ukraine War Suffered Over 4,700 Casualties' (In Korean)." April 30. https://www.yna.co.kr/amp/view/MYH20250430014600038. (Accessed: May 13, 2025)

■ Seung-ho JUNG is Associate Professor and Dean of the School of Northeast Asian Studies at Incheon National University.

■ Translated and edited by Chaerin KIM, Research Assistant

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 208) | crkim@eai.or.kr