Chaesung Chun (Director of the Global NK Zoom & Connect Editorial Board; Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Seoul National University)

As North Korea continues to conduct missile tests, the strategic balance on the Peninsula and the region cannot remain intact. North Korea is motivated to acquire missile capabilities that can strike U.S. homeland, complicating U.S. deterrent strategies in the future. As the U.S. cannot rely solely on retaliation for its deterrence, the further development of Ground-based Midcourse Defense (GMD), the only deployed missile defense system as of now, will draw more attention. However, as North Korea succeeds in developing solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) using transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) and even multiple independent reentry vehicle (MIRVed) ICBMs, the U.S. will reevaluate the reliability of its missile defense system. U.S. vulnerability to nuclear missile attacks is not a security concern limited only to Washington. It poses severe threats to the non-proliferation regime and the credibility of extended deterrence for its allies. U.S. lack of certainty in its deterrence-by-denial capability will raise concerns regarding the decoupling of security in South Korea and Japan. Seoul and Tokyo are then likely to develop larger interests in various nuclear arming options, as manifested in a recent discussion in Japan regarding nuclear sharing. High priority on the North Korean nuclear problem and solid security reassurance from the U.S. will be essential to alliance management.

The rapid development of North Korean missile capabilities leads to the elaboration and the cooperation of the missile defense system both in the U.S. and South Korea. The U.S. will put more resources in developing a missile defense (MD) system not confined to GMD, and South Korea will also consider options of deploying more Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAADs) and developing multi-layered MD systems. China has complained that more elaborated MD systems destabilize the balance of vulnerability between Washington and Beijing and heavily criticized South Korea’s acceptance of the U.S. Forces Korea’s THAAD system. China now has a stronger reason to solve the North Korean nuclear crisis with the U.S. and South Korea. It is time to fundamentally reconsider diplomatic options based on multilateral cooperation to solve the issue.

Leif-Eric Easley (Associate Professor of International Studies at Ewha Womans University)

The new South Korean administration should emphasize that its policy toward North Korea is one of reciprocity, not escalation. Economic incentives such as sanctions relief may be contingent on progress toward denuclearization, but humanitarian assistance can be offered separate from politics and dialogue is possible without preconditions. The new government’s rhetoric on inter-Korean relations can be moderate and disciplined even as Seoul strengthens deterrence capabilities with Washington.

Effective policy also requires attention to sequencing. For the sake of alliance readiness, it is better to scale up U.S.-ROK combined field exercises before strategic asset visits to the region. Operational plan (OPLAN) revisions ought to be completed before transfer of wartime operational control (OPCON). To prioritize North Koreans’ welfare and future transitional justice, the new administration could approve non-governmental organizations’ requests to send aid to the North and engage the defector community in the South before wading into the controversial leaflet issue. Finally, it makes strategic sense to improve relations with Japan before trying to find a road to Pyongyang through Beijing.

Jihwan Hwang (Professor of International Relations at the University of Seoul)

The incoming administration’s North Korea policy should reflect a nonpartisan and bipartisan disposition, moving beyond ideological conflicts between conservatives and liberals. For the past 30 years, South Korea’s North Korea policy has been associated with specific ideologies and political parties, causing domestic partisan conflicts. While conservatives believed that sanctions and pressure would trigger change in North Korea, progressives considered engagement, exchange, and cooperation to be key. In hindsight, both approaches were ineffective. The Yoon administration needs to set nonpartisan targets and pursue bipartisan policies through a flexible approach that is unbiased toward certain ideologies or prejudices. In other words, Yoon’s North Korea policy should not be limited within the bounds of domestic ideologies, but should take into account both internal and external factors.

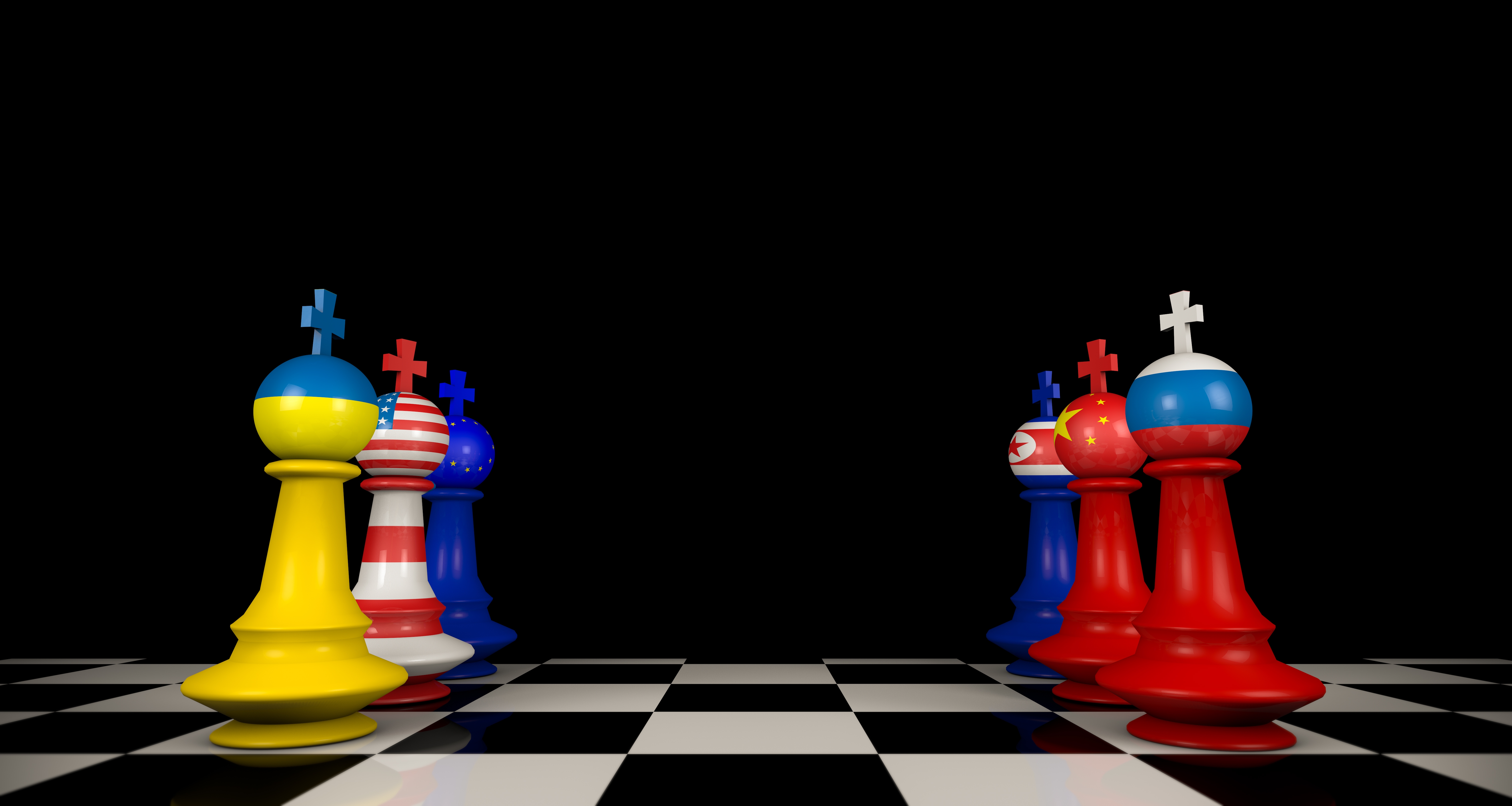

The biggest challenge facing the Yoon administration is to establish a strategic position amid the deepening U.S.-China conflict. Over the past few years, the U.S. and China have competed over global hegemony through the Indo-Pacific strategy and Belt and Road Initiative, respectively. This has had a considerable impact on the design and implementation of their North Korea strategies. Following the division of the Korean Peninsula, the North Korea policy environment has continually changed over the course of three eras – the Cold War period, the U.S. ‘Unipolar Moment,’ and the U.S.-China strategic competition. Amid intensifying U.S.-China tensions, South Korea is likely to be put in a strategic dilemma; a Washington-friendly policy would trigger Beijing to respond with hostility and vice versa. Seoul should strive to create strategic space rather than passively responding to the U.S.-China competition.

On the domestic front, the incoming administration should actively pursue peace on the Korean Peninsula and build a foundation for unification by encouraging change in North Korea. Unless Pyongyang decides to alter its national strategy, the North Korea crisis is likely to persist. In the long run, the administration should induce North Korea to break away from hyper-securitization and the byungjin line of simultaneous economic and nuclear development and shift its priorities toward economic development and public welfare. Above all, Seoul should draw the support of North Koreans, as in the case of East Germany. A true North Korea/unification policy should be able to win North Koreans over. A shift in North Korea’s national strategy, along with the free will of North Koreans, will be able to change the nature of inter-Korean relations. It is necessary to instill a perception that progress in inter-Korean relations and unification are in the interests of both Koreas. A North Korean policy that is in the likes of North Koreans is also a democratic unification policy.

Yang Gyu Kim (Principal Researcher at the East Asia Institute)

The Yoon administration should avoid the label of putting forth a complete pro-American policy excluding China. It should craft a North Korea policy that is fully aware of the room for maneuver in between Washington and Beijing’s moves. Through the “Indo-Pacific Strategy” released in February, the U.S. clearly defines its policy toward China as strategic competition. The document focuses on shaping the strategic environment “maximally favorable to the U.S.” rather than engaging or changing China and seeks to assemble all like-minded countries that share U.S. values and interests in this world of a great confrontation between democracy and authoritarianism. On the other hand, China aims to buy time, stressing that “China and the U.S. need to respect each other, coexist in peace, and avoid confrontation.” However, it has an unwavering stance on issues in which China’s core interests are at stake, such as Taiwan’s independence. Beijing will retaliate if Seoul actively seeks an extended role in potential conflicts over Taiwan or joins the open criticism against the Chinese oppressive political system, undermining its political legitimacy. Subsequently, South Korea-China relations will quickly deteriorate as they did after Seoul introduced the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system a few years ago.

It is hard to deny that South Korea’spolitical status and relative power in the international community have significantly increased over the COVID-19 pandemic. However, when it comes to deciding the policy directions of a “global pivotal state,” the Yoon administration should project South Korean diplomatic capacity and influence prudently. Especially, it is crucial to strengthen the ROK-U.S. alliance and simultaneously take heed of issue areas that China defines as its core interests. For example, the Yoon government could affirm the importance of expanding South Korea’s contribution to addressing global issues like the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and nuclear disarmament and leveling up U.S.-Japan-ROK cooperation to meet mounting security threats from Pyongyang. At the same time, it should carefully identify the policy direction of South Korea concerning issues surrounding the cross-Strait conflict, Hong Kong, and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. As long as both the U.S. and China try to avoid a confrontation, Seoul should not unilaterally shrink its strategic leeway in the region in advance.

The next administration should review essential defense capabilities required to increase the South Korean deterrence against North Korea. At first glance, it is quite natural and desirable to reinforce the military capabilities to punish Pyongyang’s ascending provocations by expanding the three-pillar system of Kill Chain, Korean Missile Defense, and Korea Massive Punishment and Retaliation. North Korea reacted to these measures by emphasizing its right to use nuclear weapons preemptively if “any forces try to violate the fundamental interests” of Pyongyang. This demonstrates that both the South and the North are eager to send credible signals of deterrence by enlarging their preemptive strike capabilities. However, as Thomas Schelling rightly argues, deterrence is always a game of punishment and assurance. If both sides are solely preoccupied with increasing punishment/offensive capabilities, the security dynamics on the Korean Peninsula could easily fall into a security dilemma and spiral. It is crucially important to manage messages and signals discreetly in this regard.

Furthermore, the Yoon administration should develop a weapon system truly conducive to buttressing deterrence. Most contemporary international crises occur when the challengers turn to fait accompli or “limited aims” strategies. In this context, what Seoul needs the most for its deterrence and defense is the conventional capabilities ensuring swift punishments at a lower level security crises such as the sinking of the ROKS Cheonan and the shelling of Yeonpyeong Island, rather than Massive Punishment and Retaliation or additional THAAD batteries. The Yoon administration should deal with North Korean nuclear threats by enlarging the “integrated deterrence“ of the ROK-U.S. alliance instead of reintroducing tactical nuclear weapons on the peninsula.

Won Gon Park (Professor of North Korea Studies at Ewha Womans University)

The Yoon Suk-yeol administration should be fully aware that Pyongyang continues to advocate its ‘double standards’ and accordingly craft and implement North Korea policy. Since September 2021, North Korea has claimed that its weapons proliferation was not directed at specific countries such as South Korea and the U.S. While the Hwasong-17 launch on March 24th, conducted in commemoration of Kim Il Sung’s 110th birthday, was reflective of North Korea’s hostile stance against the U.S, Pyongyang claimed that its launches of other missiles after September 2021 were merely designed to flaunt its weapons capabilities and resources. It insisted that weapons proliferation was solely intended for self-defense purposes. Although it is an apparent violation of international law, North Korea claims that its missile development is no different from other countries’ strategies for defense development. Pyongyang utilizes the ‘arms race’ framework, claiming that both Koreas are developing weaponry. Through this narrative, the regime obscures its illegitimate activities. Such claims have been embraced by some communities in and out of South Korea. Through this process, North Korea aims to pursue ‘normalization’ of provocation and establish itself as a de facto nuclear state.

North Korea’s motivation for disclosing personal letters exchanged by Chairman Kim and President Moon from April 20th to 21st is to place the Moon and Yoon administrations in a dichotomous relationship of ‘peace vs. competition.’ As the Moon administration has previously chosen to establish peace with North Korea, Pyongyang pushes the Yoon administration to choose conciliatory measures instead of hardline policies. In other words, North Korea strives to encourage internal disputes within South Korea. If the Yoon administration assertively responds to Pyongyang’s offensive, Pyongyang will compare Yoon with his predecessor, blaming South Korea for tensions on the peninsula.

The incoming Yoon Suk-yeol administration should establish a sophisticated and complex North Korea policy. First, it should break away from North Korea’s double standards and arms race framework. The administration should define a ballistic missile launch, a clear violation of United Nations (U.N.) resolutions, as a ‘provocation’ and cooperate with the U.S. to have the issue addressed at the U.N. Although processes led by the U.N. are unlikely to bear any fruit due to Chinese and Russian opposition, the U.N. should raise the issue of North Korea’s illegality to avoid the regime from being recognized as a de facto nuclear state. In addition, South Korea should prudently disclose its weapons system under development to prevent being involved in an unnecessary controversy concerning the arms race. No matter how advanced South Korea’s conventional weapons are, they would not be matched with nuclear weapons. In addition, South Korea’s exposé of high-tech weapons would only justify North Korea’s nuclear and missile development to China and Russia. Therefore, the incoming administration should carefully consider the effects and ground for deterrence, which means conducting effective ‘Strategic Communication’ (S.C.) toward North Korea.

In addition, the Yoon administration should establish a balanced North Korea policy. It should devise and attempt a ‘complex North Korea policy’ that incorporates both ‘peace’ and ‘competition’ rather than separating the two as dichotomous concepts. In particular, Seoul should take cautionary steps not to highlight Yoon’s hardline policy in balancing asymmetrical inter-Korean relations. It is worth it for the administration to consider proposing an unconditional inter-Korean summit immediately after assuming office. It would be groundbreaking if the administration would move forth with an agenda that discusses an array of issues, including nuclear weapons, and pursue a summit. The incoming administration’s open gesture of willingness to solve the problem through dialogue could inhibit North Korea’s provocative behavior. If North Korea refuses and continues to provoke, that choice will solely be on the regime.

Finally, the Yoon administration’s North Korea policy should refrain from unnecessarily provoking Pyongyang, taking into account the uniqueness of the regime. While the Lee Myung-bak administration’s ‘Vision 3000: Denuclearization and Openness’ is theoretically sound, it lacks consideration of North Korea’s reality. North Korea, which values regime security, prioritizes politics over its economy. In other words, Pyongyang would go as far as to ‘tigthent its belt’ to maintain the system. North Korea will acknowledge South Korea’s policy to suggest economic incentives as a reward for denuclearization as a provocation to their legitimacy. ’ü«

Ō¢Ā Chaesung Chun is the chair of the National Security Research Center at the East Asia Institute, and a professor of the department of political science and International relations at Seoul National University. He received his PhD in international relations at Northwestern University in the United States, and serves on the policy advisory committee to the South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Unification. His main research interests include international political theory, the ROK-US alliance, and Korean Peninsular affairs.

Ō¢Ā Leif-Eric Easley is a Professor at Ewha Womans University where he teaches international security and political economics. He publishes in academic journals regarding U.S.-ROK-Japan trilateral coordination on engaging China and North Korea. He has degrees from UCLA and Harvard and is frequently quoted in the New York Times, Washington Post and elsewhere on diplomacy in Asia.

Ō¢Ā Jihwan Hwang is Professor in the Department of International Relations at the University of Seoul. Dr. Hwang’s research interests include diplomatic policy and relationship between South and North Korea. He has published articles including “The Paradox of South Korea’s Unification Diplomacy: Moving beyond a State-Centric Approach”, “The Two Koreas after U.S. Unipolarity: In Search of a New North Korea Policy,” “The Political Implications of American Military Policy in Korea: Learning from Theoretical and Empirical Evidences” and so on. He received a B.A. in Diplomacy from Seoul National University and his M.A. in Political Science from Seoul National University and University of Colorado. He received a Ph.D. in Political Science from University of Colorado.

Ō¢Ā Yang Gyu Kim is a Principal Researcher at East Asia Institute and a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science and International Relations at Seoul National University. He holds a Ph.D. in International Relations from Florida International University (2019) and received his Master’s (2014) and Bachelor’s degrees (2008) in International Relations from Seoul National University. Kim was a Visiting Scholar at the Arnold A. Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University (2020-2021). He also taught IR theory, security, and foreign policy courses at Florida International University as an Adjunct Professor (2020-2021). Kim joined the Ph.D. program with a Fulbright Graduate Study Award and received the Smith Richardson Foundation’s “World Politics and Statecraft Fellowship” award for his dissertation work. Kim’s research focuses on international security, including coercive diplomacy, nuclear weapons strategy, power transition, U.S.-China relations, and North Korea. His recent works include “At the Brink of Nuclear War: Feasibility of Retaliation and the U.S. Policy Decisions During the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis” and “The Feasibility of Punishment and the Credibility of Threats: Case Studies on the First Moroccan and the Rhineland Crises.”

Ō¢Ā Won Gon Park is a Professor in the Department of North Korean Studies of Ewha Womans University. He received his Ph.D. from the Department of International Relations at Seoul National University. He studied the ROK-U.S. alliance and North Korea for 18 years at the Korea Institute for Defense Analyses. He has previously served as a professor of international studies at Handong Global University. Currently, he is a member of the Policy Advisory Committee of the Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs. His primary research areas include the ROK-U.S.

Ō¢Ā Typeset by Seung Yeon Lee, Research Associate

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 205) | slee@eai.or.kr