A Study on Humanitarian Aid to North Korea

Commentary | July 21, 2022

Juhyun Um

Secretary General, Medical Aid for Children

In this Commentary, Juhyun Um, Secretary General at Medical Aid for Children, provides an overview of international and South Korean aid initiatives in North Korea and examines North Korea’s current perspective on humanitarian assistance. The author analyzes that Pyongyang’s official refusal of humanitarian assistance in 2014 is a multidimensional issue that encompasses the health and welfare of North Koreans, the regime’s commitment to remain self-reliant, and the new Cold War order. Dr. Um proposes that in pursuing peace on the Korean peninsula, Seoul should strive to find ways that mutually respect the interests of both Koreas rather than push for a unilateral humanitarian assistance policy.

The keynote of the Yoon Suk-yeol administration’s North Korea policy is an “audacious plan.”

In his inaugural address, Yoon stated: “If North Korea genuinely embarks on a process to complete denuclearization, we are prepared to work with the international community to present an audacious plan that will vastly strengthen North Korea’s economy and improve the quality of life for its people.” This became the basis for his administration’s North Korea policy. Even after North Korea disclosed its first confirmed Omicron case on May 12, the Yoon administration stated that it would continue to provide humanitarian aid, should North Korea request it.

However, non-governmental organizations that have long been at the forefront of inter-Korean exchange and cooperation interpret the current administration’s stance and remarks to mean that the administration will do nothing to improve long-suspended inter-Korean relations. The “audacious plan” is equivalent in all but name to the Lee Myung-bak administration’s policy on North Korea, “Vision 3000: Denuclearization and Openness,” which ultimately damaged inter-Korean relations and was rejected by North Korea. In addition, South Korea, as the tenth largest economy in the world, is inherently responsible for providing humanitarian aid to North Korea as it is obliged to partake in the global mission of providing sustainable aid to countries or entities undergoing humanitarian crises. As the obligation to provide humanitarian aid is universal in nature, provision to North Korea cannot be singled out and excluded.

The problem lies in the fact that the government is recycling a North Korea policy that has already been pursued by a previous administration and rejected by North Korea. However, it is worth noting that detailed North Korea policies to be implemented by an incoming administration are typically brought forth during the second year. In the case of the Yoon administration, the “audacious plan” is a product of several North Korean policymakers active during the Lee Myung-bak administration, who have subsequently been appointed to roles in the Yoon administration. Therefore, it can be deduced that the said “plan” provides a general direction for Yoon’s North Korea policy; Yoon is expected to release a new detailed set of North Korea policies reflecting its aspirations to improve inter-Korean relations later on.

Accordingly, as an expert in the field of North Korean humanitarian aid, I review the past 30 years of inter-Korean humanitarian aid, examine North Korea’s current stance on humanitarian assistance, and discuss the future of aid provision. Through this, I hope to contribute towards a North Korea policy that is based on an understanding of the situation surrounding humanitarian aid to North Korea that stimulates inter-Korean exchange and cooperation.

The Reality of Humanitarian Aid to North Korea

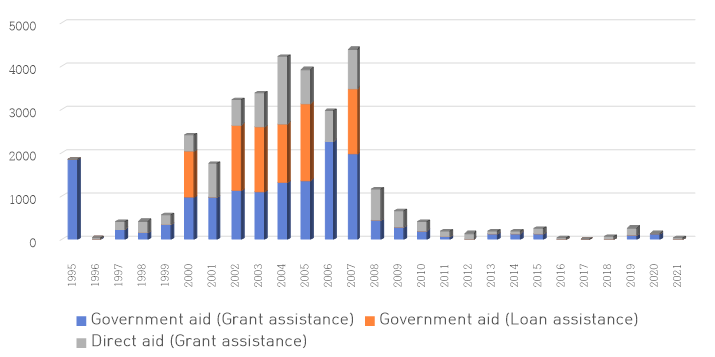

Humanitarian aid was first provided to North Korea in 1995, when it officially requested assistance from the United Nations (UN) for emergency flood damage. On September 12, 1995, the UN appealed for relief aid for North Korea represented by a UN agency. This also marked the start of South Korean humanitarian aid initiatives in the North.

Over the course of the past 30 years, the scale of humanitarian aid provided to North Korea varied depending on the present ruling party. Nonetheless, various projects were attempted during this period. To illustrate, South Korean humanitarian aid initiatives in North Korea began in 1995. Following the first inter-Korean summit in 2000, such initiatives transformed into development cooperation projects. At Medical Aid for Children, our projects donating medicine and nutritional supplements evolved into projects supporting pharmaceutical facilities and the acquisition of active pharmaceutical ingredients. Later, the scope of the projects expanded further to include hospital modernization.

However, Lee Myung-bak’s inauguration in 2008 reversed this trend—the Lee administration ceased development cooperation initiatives and limited the scope of humanitarian assistance to aid supporting infants and vulnerable people outside Pyongyang. The Lee administration denied approval on the export of materials for development cooperation projects, marking a return to pre-2008. [2] In response, non-governmental organizations argued that initial emergency humanitarian aid projects tend to evolve and expand into development cooperation projects over time as the beneficiary may strive to bolster their autonomy and ensure the project’s sustainability. Nonetheless, the government remained committed to its initial policy. As seen in the figure above, aid to North Korea decreased by 25% in 2008.

The Park Geun-hye administration, which came to power in 2013, announced its North Korea policy in Germany in 2014. However, following Park’s “Dresden Declaration,” Pyongyang announced that it would no longer accept humanitarian aid from South Korea, having concluded that the conditions for aid provision are the same as that of the previous administration. [3] Likewise, North Korea’s refusal of South Korean humanitarian aid is not a sudden development; it has not received any aid since 2014.

Kim Jong-Un’s Perception of Humanitarian Aid

Kim Jong-un came into power in 2012—this is after the two Koreas stopped engaging in humanitarian initiatives in earnest. While Kim may have inherited most of his father’s policies as power in North Korea is dynastic, transferred from father to heir, this was not the case for humanitarian assistance policy. The Kim Jong-un regime’s policy reflects a dramatic departure from that of Kim Jong-il. In 2014, Kim Jong-un rejected South Korean humanitarian aid, and in 2019, he ordered that the regime reduce the number of international organizations residing in Pyongyang. [4] This clearly demonstrated his aversion to humanitarian aid.

Moreover, there have been distinct changes in the nature of declarations and joint press releases issued by the two Koreas. In 2007, after the first meeting of the ‘Subcommittee on Health and Medical and Environmental Protection between South and North Korea’ to discuss modernizing hospitals in Sariwon, the majority of the ensuing agreement focused on what South Korea would provide for North Korea, including modernizing the People’s Hospital of Sariwon, constructing a sanitary cotton factory, and providing preventive drugs and refrigerated transportation devices for infectious disease control. [5] In contrast, the joint press release of the Inter-Korean Health and Medical Subcommittee, which was released in November 2018, called for information exchange to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and cooperation on the diagnosis and prevention of infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and malaria. In other words, this statement reflected the two Koreas’ will to cooperate on projects that meet their needs. [6]

It seems that Kim Jong-un views humanitarian aid as a mechanism used to disparage the prevailing system and his regime. Furthermore, so long as UN Resolution 2397 (passed on December 22, 2017) remains in effect, it will be difficult for North Korea to receive humanitarian aid. This is not just a one-dimensional issue, where Kim Jong-Un wants, on one hand, to save face and receive external aid, but on the other, is unwilling to accept aid from the South and the international community. Rather, this is more fundamental problem emerging from changes in the domestic and international environment.

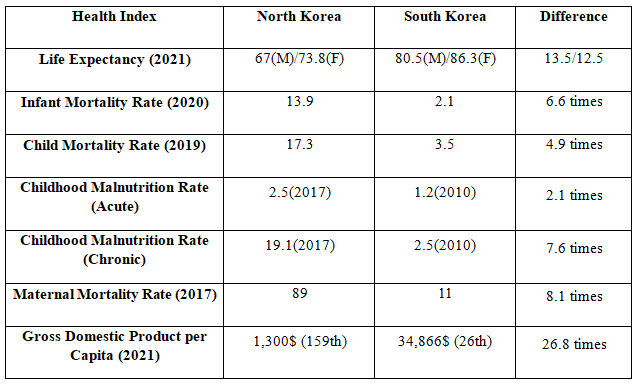

First, since Kim Jong-un assumed power, North Korea’s health index and the malnutrition crisis have improved. Of course, compared to developed countries like South Korea, living conditions are still difficult and inadequate. However, improvements are clearly demonstrated by North Korea’s health index from the 1990s through the present. For instance, the infant mortality rate decreased from 42.1% in 1995 to 28.5% in 2005, 18.5% in 2015, and 13.9% in 2020. Similarly, the child mortality rate (under-5) decreased from 72.8% in 1995 to 33% in 2005, 21.1% in 2015, and 17% in 2021.

[7]

Improvements in the status of infectious and nutritional diseases are particularly noticeable. Health indices on infectious and nutritional diseases in 2000s are lower than those in the 1980s, during which health conditions in North Korea were at their best. However, the problem is that other indicators, such as those concerning chronic diseases, show no signs of improvement or are worse than before. Though progress was made through long-term humanitarian aid programs, it has now come to a standstill. It is imperative for North Korea to develop and stimulate economic growth in order to expect further improvements in its health indices.

Furthermore, Kim Jong-un participated in discussions on economic development during the 2018 inter-Korean and DPRK-U.S. summits. However, due to the collapse of the Hanoi Summit, inter-Korean and international relations failed to improve. Then, in December of the same year, Kim declared a “head-on breakthrough battle,” adopting an extreme policy of self-reliance at the Fifth Plenary Meeting of the 7th Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, using the slogan of “Let’s live our own way.” [8] This “head-on breakthrough battle” can be understood as a return to the past—asking for as little help as possible and relying on the nation’s own capabilities to overcome its domestic struggles.

For such a policy to succeed, both government officials and citizens, who have become accustomed to receiving outside help for nearly 30 years, have to adjust their point of view. In other words, they have to reestablish a sense of agency, independence, and self-reliance, which has formed the ideological basis for the regime since the state’s initial establishment. Whether the current regime can lead such a change will determine whether the regime can guarantee its own future.

Third, the international community appears to be approaching a new Cold War order. A clear ideological confrontation offers favorable conditions for North Korea to identify who its foes and allies are. This is likely to adversely impact inter-Korean relations. North Korea has long feared that ‘foreign aid’ is a guise for invasion, a means for subjugation and looting. [9]

In fact, since disclosing its first confirmed Omicron case, the Kim Jong-un regime has been unresponsive to the material support contributed by South Korea and international organizations, but has accepted supplies and manpower from China. [10] As such North Korea must prioritize strengthening relations with its allies in order to protect its system.

Prospects for Humanitarian Aid to North Korea

Humanitarian assistance is available to recipient countries who will request and accept it, but at present, North Korea has neither the will nor the need to receive aid. Under these circumstances, there is only one condition under which it would be possible to provide humanitarian aid to North Korea—by waiting for Pyongyang to ask for help on its own. One would expect that it would eventually face the same difficulties it experienced in the mid-1990s. However, this is no different from waiting for North Korea to collapse, a confrontational perspective espoused by South Korea for more than 70 years.

Therefore, if we want to pursue peace on the Korean Peninsula and the sustainable development of both Koreas, our only choice is not to offer humanitarian aid, but rather to try and solve the more fundamental problem at hand by finding ways to maintain an attitude of mutual respect.

[1] Ministry of Unification. “Statistics.”

[2] According to data submitted by the Ministry of Unification at the request of Representative Gu Sang-chan of the Saenuri Party during the 2011 parliamentary audit, there were no government approvals from 2006 to 2008, 21 in 2009 and 36 in 2010.

[3] Cho, Jung-hoon. “Humanitarian Assistance to North Korea: ‘The Government’s ‘Self-defeating Behavior.’” Tongil News. May 20, 2014.

[4] Ahn, Yoon-seok. “Former Head of the UNDP Pyongyang office, ‘Reduction of UN staff in North Korea Sanctions is a Move Against Sanctions and for Greater Control.” SPN Seoul Pyongyang News. September 8, 2019.

[5] Ministry of Unification. 2008 White Paper on Korean Unification. 2008. 98.

[6] Ministry of Unification. 2019 White Paper on Korean Unification. 2019. 112.

[7] Statistics Korea.

[8] “Report on the Fifth Plenary Meeting of the 7th Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea.” Rodong Sinmun. January 1, 2020.

[9] Park, Moon-sung. “Johnson’s Evil ‘Foreign Assistance’ Plan for Invasion and Exploitation.” Rodong Sinmun. February 12, 1968.

[10] Lee, Seol. “First Official Release of COVID-19 Vaccine Aid to North Korea...Focus on Scale and Target.” News 1. June 3, 2022.

■ Ju-hyun Um is the Secretary General of Medical Aid for Children. She started inter-Korean health and medical exchanges and cooperation in 2002 and conducted the projects with North Korea for 20 years. During that period, she visited North Korea approximately 50 times times, carried out the modernization projects for Child Nutrition Management, Daedonggang District Hospital, and Ministry of Railways Hospital, Railway Hygiene Defense Station, Mangyeongdae Children's Hospital. She began research on the North Korean health care system in 2012, in order to contribute to securing the right to health for both Koreas by strengthening public of the health care system and the improving the quality of health care services through inter-Korean health care exchanges and cooperation. She obtained a doctorate in 2020 for “Research on the North Korea Healthcare System Establishment Process.”

■ Typeset by Seung Yeon Lee, Research Associate; Sarah MacHarg, Intern

For inquiries: 02 2277 1683 (ext. 205) | sleeeai.or.kr

Inter-Korean Relations and Unification

President Yoon's Trip to Madrid: Rethinking Seoul's Policies toward Moscow, Beijing, Tokyo, and Pyongyang

Yang Gyu Kim | 11.July.2022

The Yoon-Biden Summit and Prospects for the Yoon Administration’s North Korea Policy

Young-ho Park | 21.June.2022

Prospects for DPRK-China Relations in 2022 and Challenges for the Yoon Administration

Bong Sup Shin | 08.June.2022

LIST